Making Enchiladas: A Coming-of-Age Tale

For many people in my life there is no category for living in a place like Mozambique. Though it’s becoming more normal for me each day, it often results in a variety questions from other people. But there is one question that is always asked, usually with great concern and trepidation.

“What do you eat there?”

If I am eating with Mozambican friends, the meals are pretty standard. Sometimes rice and beans, sometimes ixima (SHEE-ma, a type of cornmeal mush) and beans, sometimes greens, sometimes fish, sometimes chicken, and I once received goat spaghetti. Occasionally there are some more interesting meat varieties offered, but that’s rare.

Ixima

But on a regular day, my food is pretty American. More vegetables and less preservatives than America, but pretty American nonetheless.

The main difference is the way that it’s made.

When I had this conversation before I left for Mozambique people would ask, “Can you cook?” And I would reply, “Yeah, sure.” I lived outside of my parents’ house for 4 years before coming here and managed to feed myself every day. And, usually, I cooked well. Or so I thought.

But coming here opened my eyes to a harsh reality.

I have no idea how to cook.

I have no idea how to cook things from scratch, that are no instant, that can be made without a microwave or electricity, and can be made with the ingredients I have available here.

But before we get to how to get the meal, let me talk about how to get the ingredients.

Almost all of the food here is relatively local and sold to the market by farmers. On Saturdays a friend drives my roommate and I to the Central Mosque, where fruit vendors and men selling phone credit are lined up along the wall. We scope out the best bananas, the healthiest looking pineapples, and the largest mangoes. No berries or peaches here, but several tropical options.

Then we head inside the market. The market is mostly covered and composed of countless numbers of stalls selling all manner of things. We thought it was completely covered until it rained one day and we found ourselves wading through mid-shin deep water with our bags of produce. One person and a motorcycle can fit in the walkway scattered with vendors yelling "Karibu!" (welcome), children selling samosas, and men playing checkers. First we walk through the "home goods section," mostly Somali immigrants selling dishes and buckets, with one man selling brown leather sandals that I hope to buy someday. Then we go through the clothing section, where stall after stall is filled with the brightly colored fabric that all of the women wear or large piles of used clothing from all over the world. Kapulanas are mainly worn as skirts and head coverings, but you can do just anything with kapulana fabric. Anything.

Then, assuming we make the right turn the first time, we are led into the produce section. This large section is full of tables heaping with onions, potatoes, rice, beans, coconuts, greens, and all kinds of other vegetables. We make our way around, conversing in Makua, Portuguese, Swahili, French, and occasionally English until we find the best prices for the best selections. After looking around a little bit more, we head back out of the market.

I haven't built up the confidence or found a good opportunity to take pictures of the market just yet, so this one of the market entrance belongs to travel bloggers (https://headoverheels2014.com/category/mozambique/) who interestingly say, "For any travelers I definitely recommend Montepuez. Possibly my favourite town of the whole journey."

Thanks to some new developments in town, Montepuez now has a small supermarket run by some Pakistani men. It was all the rage when it came to town because it has aisles and receipts. It’s a little more expensive, but much easier to find things than in the market and you can get things there – like cheese, jam, and good chicken – that we don't usually get unless we’re in Pemba, which is two hours away.

All this to say, meal planning and grocery shopping is a bit different. It takes a long time to get your groceries, usually with multiple stops around town, and the markets may not have what you want. Maybe it’s not tomato season. Maybe the bread oven is broken. Maybe the storeowner of the one store that had American mayonnaise got deported. Maybe you’re taking the twenty minute walk home and you’re sweating and your bag breaks and your skirt is falling off. Definitely a much more riveting journey than your average trip to Kroger.

The cooking process is pretty similar to what I did in America – just more steps. Most nights we cook with a gas stove/oven. And everything is made from scratch.

One night I was talking to my friend Alyssa while she was making enchiladas, which inspired me to do the same. But the way we went about it was a little different.

She used chicken, but I had to use beans. So, the process started out slow, with the hours-long process of simmering beans. But I occupied my time by attempting to make tortillas. Alyssa could buy hers, but I got to have the humbling experience of making my own. I’m confident that cooking here will produce strong character in me.

Now, I have seen people make tortillas before. One of the men who cooks for my neighbors, Taju, is a tortilla-making master. He is like the Yoda of tortilla making, using the force to craft huge amounts of flawless tortillas. I watch him take the perfectly proportioned dough, throw it onto a slab, and in seconds he has a perfectly round and perfectly thin tortilla. And I know that there are millions of people around the world who are able to do this. But friends, the ability to make a tortilla is a gift from God and he decided to make it a thorn in my flesh, because I have spent many hours trying to make tortillas and I have not made much progress.

My dough is too sticky. Add flour, you say. Well, 8 cups of flour later it is still too sticky. And, as I mentioned before, I can’t just go out and get some more real quick. So, I roll out my semi-round tortillas, patching them back together as the rolling pin rips them apart, trying to reform them into a semblance of a circle. Eventually I have small, semi-circle pieces of flatbread that I call tortillas that I do my best not to break when I wrap them around the contents.

I finish my beans and add tomato, pepper, onion, and rice. I run next door to my neighbor’s freezer, where I house my cheese. Since cheese is a delicacy here, and could only be found in Pemba before about a month ago, we buy it in large blocks and freeze it. I grate my frozen cheese into my bean mixture. I fill my flatbread tortillas and try to roll them up without them falling apart. It was a success. I season them with cilantro and “sour cream” (which is actually yogurt) and put them in the oven.

Now, my oven is the greatest mystery of all. You see, when you turn it on it begins to get hot, but it has no temperature control, so it just keeps getting hotter. I wait about 10 minutes, then turn it off. Wait about 10 minutes more, and turn it back on. I do this until the enchiladas are ready to be eaten.

Alyssa texted me a picture of her enchilada, which she dropped on the floor. That just goes to show that enchiladas are difficult no matter where you live.

Not that something like that would stop anyone from eating something as delicious as an enchilada

I pull my beautiful creation out of the oven.

I marvel at the art of the enchiladas.

I take a picture of my enchiladas, as I do with every meal, because I feel that each success is an incredible accomplishment.

Then I realize that I need a side. “Curse American culture for forcing me to believe that I need a side with my meal!” I think to myself.

But then I go to my old standby side for every meal when I forget that meals are supposed to have sides. Carrot sticks. I take my bleached carrots, peel them, and slice them.

Six hours later, dinner is served.

My organic, locally grown, locally sold, vegan bean enchiladas

So far, everything I have made here has been for the first time. I seem to have no recollection of what I ate before Mozambique, because I can never think of food that I have successfully made prior to October 2016.

Some meals have been successes.

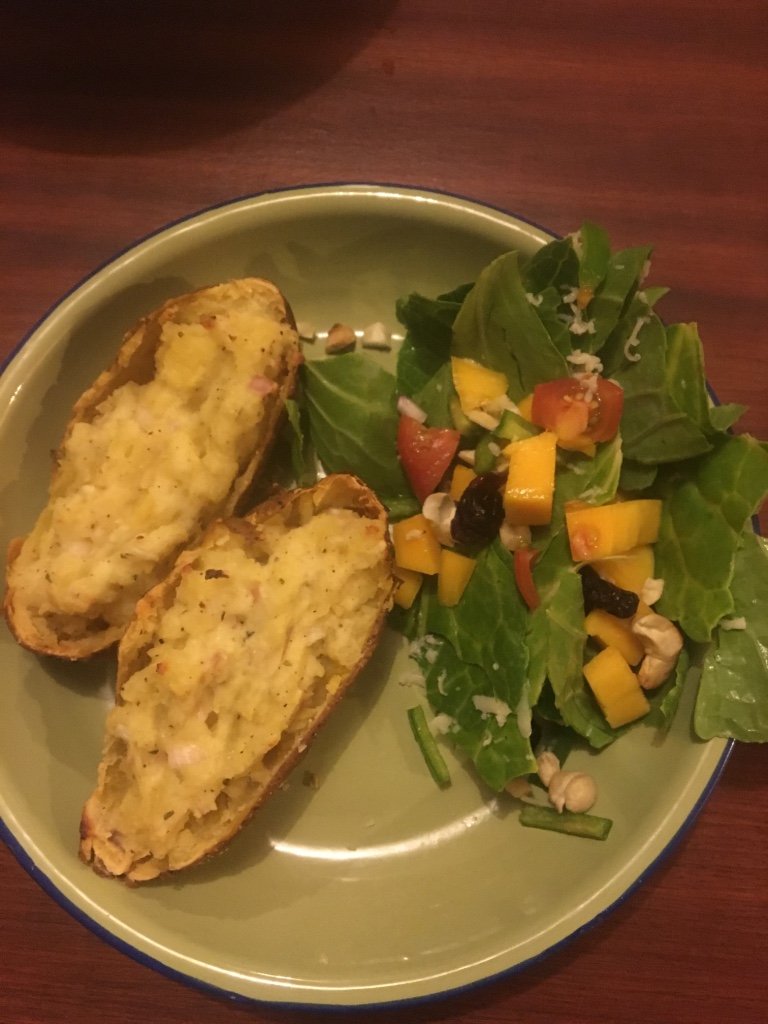

My baked spaghetti was delicious; my twice-baked potatoes were awesome; my quiche was perfectly proportioned; my salad was beautiful (much more difficult to make a salad than you would think); and I am now a confident chicken-roaster.

Stuffed Peppers

Twice-Baked Potatoes & Salad

Roasted Chicken

Some meals have been failures.

My salsa, though mostly tomatoes, has turned out white and tasted like liquid onion; my chips have blackened and filled the kitchen with smoke upon contact with the frying pan; my jambalaya has been simultaneously underdone and overdone; my coffee beans have been either completely burnt or barely done; and my corndogs, well, they speak for themselves.

Yup, these are corn dogs.

Meal planning, grocery shopping, and cooking are becoming more natural all the time. Practice makes perfect – or at least makes it better than the last time I made it. Like with most things here, I’m in progress.

So, in your prayers, thank God for bags of shredded cheese, America’s seemingly endless supply of lettuce, people who are good at making tortillas, and the fact that my gracious roommate cooks every other week.